The rogue landlord database has been live for nearly two years but has yet to become the trailblazing success it was set to be. The article below outlines the history of the database and forecasts the future of policy for the private rented sector. To hear from the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government about policy developments attend our '5th Annual Rogue Landlord Forum'

2018: The Failed Rogue Landlord Database

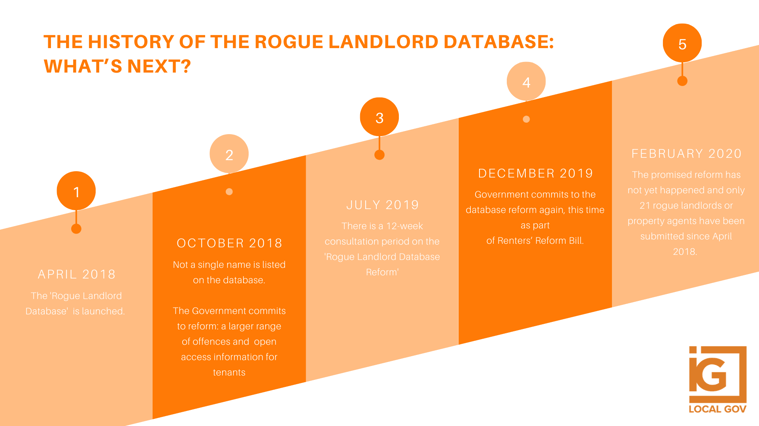

In April 2018, the Government launched the database of rogue landlords and property agents. The intention was to allow local authorities to target the most prolific offenders - those who have been convicted of banning order offences or have received at least two financial penalties within 12 months. It also aimed to encourage joint working to tackle rogue landlords working across council divisions.

The government expected around 600 names to be entered into the database, but 6 months on, not a single name had been. While the resource was available, the Government failed to mobilise councils, and councils failed to act. Alan Ward, chairman of the Residential Landlords Association (RLA) noted “the problem is that while Westminster enacts the legislation it is dependent on the political will of councils to enforce it. Research by the RLA has shown that few councils are yet to make use of the civil penalties now available to them."

After the news broke in October 2018, Theresa May decided to change the direction of the tool completely, committing to opening access to the information on the database to tenants. The move was opened to a 12-week consultation period in July – October 2019.

2019: An Open Access Database?

Once announced, support for the notion of opening access to the database was widespread. Dan Wilson Craw, director of Generation Rent, stated: "Renters have to provide references from employers and previous landlords before a landlord hands over the keys to a new flat. So it is only fair that renters get the opportunity to check that a prospective landlord doesn't have a criminal record."

Shelter’s chief executive, Polly Neate, also argued that the database “will offer renters a better chance of protecting themselves and their family.” In other words, the open database will not only act as a deterrent but a preventative measure, allowing tenants to make an informed decision about with whom they choose to rent from.

The Greater London Authorities’ (GLA) ‘Rogue Landlord and Agent Checker’ was a testament to this point. The Checker, launched by Sadiq Khan in 2018, is a database open to the public, London boroughs and the London Fire Brigade. And indeed, it has been very successful in empowering tenants: as of February 2020, the Checker was reported to have been viewed over 185,000 times, with over 2,000 offences recorded.

2020: Will this be The Year?

In the same month that Khan announced the success of his Checker, the failure of the government Database came back into focus. Data obtained through a Freedom of Information Act reveals that only 21 rogue landlords or property agents have been submitted since April 2018. This covers 38 offences, submitted by a total of 15 local authorities.

The Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government had many arguments for this reported failure: “the database is targeted at only the very worst and persistent offenders, those who have committed banning order offences” “It takes time to secure convictions or civil penalty notices for offences” “The offence must have been committed after 6 April 2018” Indeed, research shows that it now takes an average of almost half a year for courts to process claims for repossession of property.

The hope is that the initiative is a slow burner, something which broadening the scope and access could fix: with an increased range of offences and infraction, local authorities would be more empowered to reprimand landlords flagrantly flouting the law. Similarly, if the failure is an issue of engagement, by opening the information to the public, there will be an increased pressure on local authorities to utilise the tools available to them.

There are of course sceptics. John Steward, Policy Manager at the RLA, argues that we need a complete overhaul of government policy, one that will "encourage growth in the supply of rental accommodation” rather than “attacking the private rented sector." There is also the argument that, with two competing systems - the GLA’s Checker and the Government Database – neither will flourish.

In the Queens’ Speech in December 2019, the Government promised the introduction of the Renters’ Reform Bill, which, among other things, re-states the promise to deliver on the Rogue Landlord Database Reform. As the new government settles in, we await the results of the consultation and the future of private rented sector.

This article was written by Gabby Koumis.